"The Marvel Universe's greatest era starts here! In the wake of Professor X's funeral, Captain America creates a new Avengers unit comprised of Avengers and X-Men, humans and mutants working together. But the Red Skull has returned - straight out of the 1940s - and he wants to destroy all mutants! What gruesome weapon has given him dangerous new powers? Rogue and Scarlet Witch face off against the Red Skull's S-Men, Wolverine and Captain America investi gate the worldwide mutant assassination epidemic, and Havok and Thor battle the spreading infl uence of Honest John, the Living Propaganda! And when an Avenger defects, the rest must face the terrible might of the Omega Skull! Plus: Wonder Man, Wasp and Sunfire join the team - just in time for the Grim Reaper's revenge! Uncanny Avengers Assemble!"

"The future begins in the past! It's an 11th century clash of the titans as Thor batt les Apocalypse! The Avengers' ancestors are being hunted, with Rama-Tut and Kang pulling the strings, and only a young Thor can save his future companions! And in the present, the beginning of the end looms as the Apocalypse Twins debut! Why are they targeting the Celestials? What is their connection to Kang? And how is Thor responsible for their mighty power? Apocalypse's Ship attacks S.W.O.R.D., a Celestial meets a shocking fate, and the Four Horsemen of Death are' unleashed! And as the Twins' new henchmen shatter the Uncanny Avengers, Wolverine discovers the Midnight City - and immediately wishes he hadn't! When all hope dies, Ragnarok begins! Plus: Kang and the Apocalypse Twins enter the Age of Ultron!"

"It's the dark origin of the Apocalypse Twins, as Kang's true motives are revealed! A secret pact between Ahab and the Red Skull will bring horror to all mutants. But against his masters' orders, a deranged and vengeful Sentry kills an Uncanny Avenger! It's no hoax, no dream...and only the first casualty of many! To allow reinforcements from other eras, the Wasp must find and destroy the Twins' tachyon transmitter, but first she'll have to defeat the Grim Reaper. Meanwhile, the Scarlet Witch makes an impossible choice that will define her forever. And Sunfire and Rogue, without backup, must defeat the combined might of both Apocalypse Twins - or watch the end of our world! Bring on the bad guys, because Ragnarök is now!'

Uncanny Avengers is the Avengers at its very worst, a joke line up that competes with West Coast Avengers for how much of the barrel it's prepared to scrape. The idea behind it is that following the events of AvX, and the fact that people now hate and fear mutants and ever before, the Avengers have suddenly realised that maybe if they stopped punching the X-Men for more than a week people might learn to trust them. So Captain America looks to create a 'unity' team of all the X-Men and Avengers no other writer wanted; Wonder Man! Wasp! Havok! Scarlet Witch!

If those aren't names to inspire confidence, they also have Thor and Wolverine thrown in. So, just to go over that: Wonderman (was a villain in last appearance), Wolverine (unsanctioned murder squad leader), Havok (Brother to 'Terrorist' leader) and Scarlet Witch (only Avenger to ever actually commit Genocide). Fortunately, they also have Rogue ... who's a former member of the Brotherhood of Evil Mutants. So I can't see how that plan can possibly go wrong.

It's hard for me to express how much hate I feel for some of these characters. Not in a detatched, 'oh they're so annoying, but they're fictional' way, but in a very real, very visceral 'I wish they had never ever been written' way.

Scarlet Witch is a great example of that. Daughter of Magneto, chaos magic wielder and reality warper, Scarlet Witch's most famous action in the last two decades was to kill half of her own Avengers team, rewrite reality into a mutant-lead parallel universe, then destroy all but 200 mutants. She then came back and tried to hand wave it all away as being Doctor Doom's fault.

If you're looking for a reason why people hate mutant, that right there is it. She single handedly fought every superhero in the world to a standstill, then when she lost she almost destroyed a species. Wow, guys. I can't at all understand why someone might be afraid of that. You should probably put her up on stage as the face of mutant rehabilitation.

Or Havok, a guy whose very first defining action in the book is to renounce Cyclops, a flawed, but great, leader who successfully reignited mutantkind, saving his species. Then, he follows it up, by deciding he doesn't want to be called a mutant because Havok is a whinge. I hate Havok. When I say he's the third best Summers brother, you know that it's low.

You know what. There are better X-books, and better Avengers books. This is just a hot mess that nobody will remember in 5 years time. Art is lovely though.

Also Try:

Any X-Men book

Any Avengers book

Avengers Assimilate: Identity Politics in Uncanny Avengers, http://comicsalliance.com/uncanny-avengers-5-rick-remender-identity-politics-mutants/ (and Remender's response: http://www.newsarama.com/17328-remender-responds-to-uncanny-avengers-m-word-controversy.html)

Friday, December 5, 2014

Wednesday, November 19, 2014

Idiot America, Charles Pierce

"The three Great Premises of Idiot America:

· Any theory is valid if it sells books, soaks up ratings, or otherwise moves units

· Anything can be true if someone says it loudly enough

· Fact is that which enough people believe. Truth is determined by how fervently they believe it

Pierce asks how a country founded on intellectual curiosity has somehow deteriorated into a nation of simpletons more apt to vote for an American Idol contestant than a presidential candidate. But his thunderous denunciation is also a secret call to action, as he hopes that somehow, being intelligent will stop being a stigma, and that pinheads will once again be pitied, not celebrated. Erudite and razor-sharp, Idiot America is at once an invigorating history lesson, a cutting cultural critique, and a bullish appeal to our smarter selves."

This is an entertaining, but shallow look at where America's unreasonable distrust of reason has come from. Unfortunately it's a little bit too please with itself and comes across as a caricature of smug liberalism, exhausting the things it actually has to say about 20 pages in and then continuing on for much longer than is really required.

I've got a lot of time for people who want to raise the level of public discourse in the US, who believe that vilifying science and education, raising up the ignorant and creating an atmosphere of debate where there's two sides to every story is ridiculous and damaging but this book is more focused on cheap point scoring and ad hominem attacks, plus a peculiar fascination with the work of James Madison and obscure 19th Century cranks and oddballs.

The root of the problem comes from Pierce's idea that there's something noble and righteous about being slightly unhinged and coming up with crazy iideas. He just thinks they've become too mainstream and America has followed them too far into the wilderness. This misses the point, that education, science and the progression of knowledge invalidate the crank altogether.

Not really worth reading, in the end, but it does have a beautiful cover illustration, and the book itself has the heft and weight of something much better than itself.

· Any theory is valid if it sells books, soaks up ratings, or otherwise moves units

· Anything can be true if someone says it loudly enough

· Fact is that which enough people believe. Truth is determined by how fervently they believe it

Pierce asks how a country founded on intellectual curiosity has somehow deteriorated into a nation of simpletons more apt to vote for an American Idol contestant than a presidential candidate. But his thunderous denunciation is also a secret call to action, as he hopes that somehow, being intelligent will stop being a stigma, and that pinheads will once again be pitied, not celebrated. Erudite and razor-sharp, Idiot America is at once an invigorating history lesson, a cutting cultural critique, and a bullish appeal to our smarter selves."

This is an entertaining, but shallow look at where America's unreasonable distrust of reason has come from. Unfortunately it's a little bit too please with itself and comes across as a caricature of smug liberalism, exhausting the things it actually has to say about 20 pages in and then continuing on for much longer than is really required.

I've got a lot of time for people who want to raise the level of public discourse in the US, who believe that vilifying science and education, raising up the ignorant and creating an atmosphere of debate where there's two sides to every story is ridiculous and damaging but this book is more focused on cheap point scoring and ad hominem attacks, plus a peculiar fascination with the work of James Madison and obscure 19th Century cranks and oddballs.

The root of the problem comes from Pierce's idea that there's something noble and righteous about being slightly unhinged and coming up with crazy iideas. He just thinks they've become too mainstream and America has followed them too far into the wilderness. This misses the point, that education, science and the progression of knowledge invalidate the crank altogether.

Not really worth reading, in the end, but it does have a beautiful cover illustration, and the book itself has the heft and weight of something much better than itself.

Tuesday, October 28, 2014

The Shining Girls, Lauren Beukes

"The girl who wouldn’t die – hunting a killer who shouldn’t exist.

A bizarre little beauty of a book, this time travel serial killer murder mystery who-dunnit, is, as that description suggests, a mish-mash of all sorts of genres that shouldn't really work but do.

The story itself is lithely written, racing along at a solid pace. Both the heroine, Kirby, and the villain, Harper, are terrifically written, with neither given the treatment of flawlessness; Harper is a monster, but also a victim of circumstance, petty, vindictive, cruel and murderous, but also weighed down upon by the House, and his own half-created destiny. Kirby is broken, but rarely sympathetic, she's shattered into cold edges, and like Gone Girl this a story of flawed human beings who often exert little in the way of humanity.

Trotting between eras, the real skill of The Shining Girls is in picking out victims that do pull at the herat strings; Harper's task, to kill off women with something exceptional about them is horrifyingly, cruelly misogynistic and utterly readable. In choosing such an obviously 'good' group to target Beukes removes the need to make them 'good' people; their lives are testament to that, and so Kirby's own flaws mean very little compared to what she could have been. Her survival is in a world that she is out of place in, her achievements after are through a prism of her broken nature.

Really enjoyable book. Perfect thriller.

Also Try:

Audrey Niffenegger, The Time Travelers Wife

Robert Harris, Silence of the Lambs

Dean Koontz, From The Corner of His Eye

In Depression-era Chicago, Harper Curtis finds a key to a house that opens on to other times. But it comes at a cost. He has to kill the shining girls: bright young women, burning with potential. He stalks them through their lives across different eras, leaving anachronistic clues on their bodies, until, in 1989, one of his victims, Kirby Mazrachi, survives and turns the hunt around."

A bizarre little beauty of a book, this time travel serial killer murder mystery who-dunnit, is, as that description suggests, a mish-mash of all sorts of genres that shouldn't really work but do.

The story itself is lithely written, racing along at a solid pace. Both the heroine, Kirby, and the villain, Harper, are terrifically written, with neither given the treatment of flawlessness; Harper is a monster, but also a victim of circumstance, petty, vindictive, cruel and murderous, but also weighed down upon by the House, and his own half-created destiny. Kirby is broken, but rarely sympathetic, she's shattered into cold edges, and like Gone Girl this a story of flawed human beings who often exert little in the way of humanity.

Trotting between eras, the real skill of The Shining Girls is in picking out victims that do pull at the herat strings; Harper's task, to kill off women with something exceptional about them is horrifyingly, cruelly misogynistic and utterly readable. In choosing such an obviously 'good' group to target Beukes removes the need to make them 'good' people; their lives are testament to that, and so Kirby's own flaws mean very little compared to what she could have been. Her survival is in a world that she is out of place in, her achievements after are through a prism of her broken nature.

Really enjoyable book. Perfect thriller.

Also Try:

Audrey Niffenegger, The Time Travelers Wife

Robert Harris, Silence of the Lambs

Dean Koontz, From The Corner of His Eye

Double Down: Game Change 2012, Mark Halperin and John Heilemann

"Double Down picks up the story in the Oval Office, where the president is beset by crises both inherited and unforeseen—facing defiance from his political foes, disenchantment from the voters, disdain from the nation’s powerful money machers, and dysfunction within the West Wing. As 2012 looms, leaders of the Republican Party, salivating over Obama’s political fragility, see a chance to wrest back control of the White House—and the country. So how did the Republicans screw it up? How did Obama survive the onslaught of super PACs and defy the predictions of a one-term presidency? Double Down follows the gaudy carnival of GOP contenders—ambitious and flawed, famous and infamous, charismatic and cartoonish—as Mitt Romney, the straitlaced, can-do, gaffe-prone multimillionaire from Massachusetts, scraped and scratched his way to the nomination."

This is, for me, probably the best book on political action, American politics and campaigns ever written. It's utterly fantastic, and hyperbole-busting stuff, the kind of writing which clutches at you and drags you with it to the finish from the very first page.

With surgical incisiveness Halperin and Heilemann dissect the hows and whys of the 2012 Presidential Campaign, examining in detail the merits and failures of the Republican and Democrat bids for the White House. From the excoriation of the performances on the Right, to the shellacking of Obama's record and position, the book shows how either side could have truimphed, but how the Republicans intransigence and mistakes sank their run and handed Obama the victory.

But rather than just looking at the two candidates and their rivals, the book also examines in depth the teams and outside agents who ran the race, from those in charge of Super PACs, to prominent critics and champions, to the donors, backers and stirrers of modern politics in Washington. Insightful, withering and witty, the book is paced like a thriller and written with a verve and style that belies the seemingly dry subject matter.

So worth reading, I've ordered the first book, chronicling the 2008 campaign, to keep going.

Also Try:

Barack Obama, Audacity of Hope

Molly Ivins, Bushwhacked

Al Franken, Why Not Me?

This is, for me, probably the best book on political action, American politics and campaigns ever written. It's utterly fantastic, and hyperbole-busting stuff, the kind of writing which clutches at you and drags you with it to the finish from the very first page.

With surgical incisiveness Halperin and Heilemann dissect the hows and whys of the 2012 Presidential Campaign, examining in detail the merits and failures of the Republican and Democrat bids for the White House. From the excoriation of the performances on the Right, to the shellacking of Obama's record and position, the book shows how either side could have truimphed, but how the Republicans intransigence and mistakes sank their run and handed Obama the victory.

But rather than just looking at the two candidates and their rivals, the book also examines in depth the teams and outside agents who ran the race, from those in charge of Super PACs, to prominent critics and champions, to the donors, backers and stirrers of modern politics in Washington. Insightful, withering and witty, the book is paced like a thriller and written with a verve and style that belies the seemingly dry subject matter.

So worth reading, I've ordered the first book, chronicling the 2008 campaign, to keep going.

Also Try:

Barack Obama, Audacity of Hope

Molly Ivins, Bushwhacked

Al Franken, Why Not Me?

God's Politics, Jim Wallis

"Jim Wallis' book is a scathing indictment of the way that conservative evangelicals in the US have self-righteously attempted to co-opt any discussion of religion and politics. And, while the Right argues that God's way is their way, the Left pursues an unrealistic separation of religious values from morally grounded political leadership. God's Politics offers a clarion call to make America's religious communities and its government more accountable to key values of the prophetic religious tradition - pro-justice, pro-peace, pro-environment, pro-equality, pro-consistent ethic of life and pro-family. These are the values of love and justice, reconciliation, and community at the core of what many people believe, whether Christian or not."

The image on the front cover is misleading, because this isn't a book about George Bush, or religion and faith in politics in the sense of the 'family values' or 'religious right' crusaders. Instead, it's a thoughtful and essential examination of some of the biggest issues in contemporary culture, from war and violence, to political action, to the enviroment, and how Christians should respond.

I must confess to being slightly enraptured by it, because it is overtly Christian and resolutely progressive. Whilst some of the conclusions it reaches are the antithesis of the 'liberal' platform, they are all neatly and comprehensively wrapped in a single core fact; God loves us, and the world, and we should represent that through love and service towards others.

This for me then is the summation of what Christian life is, and the debates and wisdom contained within are challenging and enlightening to me both as a liberal christian and a Christian Liberal. Some of it I disagree with, most of it I find humbling, but none of it can be easily disregarded. For any Christian who wishes to adequately grapple with the demands of faith and politics in the 21st Century this is essential reading.

Also Try:

Shane Claiborne, The Irresistable Revolution

Sojourners, http://sojo.net/

The image on the front cover is misleading, because this isn't a book about George Bush, or religion and faith in politics in the sense of the 'family values' or 'religious right' crusaders. Instead, it's a thoughtful and essential examination of some of the biggest issues in contemporary culture, from war and violence, to political action, to the enviroment, and how Christians should respond.

I must confess to being slightly enraptured by it, because it is overtly Christian and resolutely progressive. Whilst some of the conclusions it reaches are the antithesis of the 'liberal' platform, they are all neatly and comprehensively wrapped in a single core fact; God loves us, and the world, and we should represent that through love and service towards others.

This for me then is the summation of what Christian life is, and the debates and wisdom contained within are challenging and enlightening to me both as a liberal christian and a Christian Liberal. Some of it I disagree with, most of it I find humbling, but none of it can be easily disregarded. For any Christian who wishes to adequately grapple with the demands of faith and politics in the 21st Century this is essential reading.

Also Try:

Shane Claiborne, The Irresistable Revolution

Sojourners, http://sojo.net/

The Male Brain, Louann Brizendine M.D

"Dr. Louann Brizendine, the founder of the first clinic in the country to study gender differences in brain, behavior, and hormones, turns her attention to the male brain, showing how, through every phase of life, the "male reality" is fundamentally different from the female one. Exploring the latest breakthroughs in male psychology and neurology with her trademark accessibility and candor, she reveals that the male brain:

*is a lean, mean, problem-solving machine. Faced with a personal problem, a man will use his analytical brain structures, not his emotional ones, to find a solution.

*thrives under competition, instinctively plays rough and is obsessed with rank and hierarchy.

*has an area for sexual pursuit that is 2.5 times larger than the female brain, consuming him with sexual fantasies about female body parts.

*experiences such a massive increase in testosterone at puberty that he perceive others' faces to be more aggressive.

The Male Brain finally overturns the stereotypes. Impeccably researched and at the cutting edge of scientific knowledge, this is a book that every man, and especially every woman bedeviled by a man, will need to own."

*is a lean, mean, problem-solving machine. Faced with a personal problem, a man will use his analytical brain structures, not his emotional ones, to find a solution.

*thrives under competition, instinctively plays rough and is obsessed with rank and hierarchy.

*has an area for sexual pursuit that is 2.5 times larger than the female brain, consuming him with sexual fantasies about female body parts.

*experiences such a massive increase in testosterone at puberty that he perceive others' faces to be more aggressive.

The Male Brain finally overturns the stereotypes. Impeccably researched and at the cutting edge of scientific knowledge, this is a book that every man, and especially every woman bedeviled by a man, will need to own."

Loaned to my by Jim, my Father in law, who is a counsellor and Psychologist, this is a compulsively readable breakdown of what's going on inside Men's heads through their lives, from childhood to old age, and how the competing biological drives and hormones their bodies release.

It's endlessly fascinating, both as an insight into typical human development, and for the knowledge it contains. Facts about every aspect of the brain are astonishing anyway, and to see them explain and predict the conscious and unconscious desires and demands of a person is incredibly interesting.

The mix of science and anecdotal experience is jarring, however, and the constant use of Male friends or clients of the author and their actions that provide examples and evidence to back up her claims is unnecessary. I trust that the author knows what she's discussing, and her use of case studies I can't study doesn't make it more readable or reliable.

But this is probably brilliant if you have a male child; I would certainly say it's provided insight into my own thoughts and actions, and stuff I can always use to prove JJ wrong. So that's good, anyway.

Also Try:

Louann Brizendine, The Female Brain

It's endlessly fascinating, both as an insight into typical human development, and for the knowledge it contains. Facts about every aspect of the brain are astonishing anyway, and to see them explain and predict the conscious and unconscious desires and demands of a person is incredibly interesting.

The mix of science and anecdotal experience is jarring, however, and the constant use of Male friends or clients of the author and their actions that provide examples and evidence to back up her claims is unnecessary. I trust that the author knows what she's discussing, and her use of case studies I can't study doesn't make it more readable or reliable.

But this is probably brilliant if you have a male child; I would certainly say it's provided insight into my own thoughts and actions, and stuff I can always use to prove JJ wrong. So that's good, anyway.

Also Try:

Louann Brizendine, The Female Brain

Monday, October 27, 2014

Know Why You Believe, Paul. E. Little

"Have you ever asked

Do science and Scripture conflict?

Are miracles possible?

Is Christian experience real?

Why does God allow suffering and evil?

These questions need solid answers. That's what a million people have already found in this clear and reasonable response to the toughest intellectual challenges posed to Christian belief. This edition, revised and updated by Marie Little in consultation with experts in science and archaeology, provides twenty-first-century information and offers solid ground for those who are willing to search for truth. Including a study guide for individuals or groups, the classic answerbook on Christian faith has never been better!"

Know Why You Believe is a wide casting look at the 'most common' questions that non-Christians ask; things like whether Science and History are consistent with the Biblical narrative, whether God is good, and all of the other questions you would expect. This is part of the problem; these hoary old questions have been rehashed so much that they barely provide anything new on either side. Like two grandmasters playing chess, both sides know the best moves to make and the opening gambits are simply about manouvering. It's only by going deeper that anything actually interesting or challenging can be reached.

This, however, is very much a surface level introduction, and if you're keen to just read one book and be convinced, you probably will be. It's well argued, impeccably sourced and clearly articulated, but it really is only skimming the surface. The chapter on science is no comprehensive rebuttal of The Selfish Gene or God Delusion, the two most prominent critiques of religion from Dawkins, which would be the kind of thing any Christian faced with this question in real life would need to answer.

In fact, much of its muscle comes from a reliance on Biblical exegesis and authority, a difficult position to maintain if the reader doubts the inerrancy of that text. This leaves it in a halfway house of trying to prove the Bible, whilst asserting the relevance of the Bible as the ur-text and proof. Neither legally rigorous or logically consistent, this is best read as an introduction, for a few snappy soundbites and quotes, and then moved on from, swiftly.

Also Try:

Lee Strobel, Case for Christ

Richard Dawkins, God Delusion

Karen Armstrong, The Bible: A Biography

Tom Wright, Creation, Power and Truth

These questions need solid answers. That's what a million people have already found in this clear and reasonable response to the toughest intellectual challenges posed to Christian belief. This edition, revised and updated by Marie Little in consultation with experts in science and archaeology, provides twenty-first-century information and offers solid ground for those who are willing to search for truth. Including a study guide for individuals or groups, the classic answerbook on Christian faith has never been better!"

Know Why You Believe is a wide casting look at the 'most common' questions that non-Christians ask; things like whether Science and History are consistent with the Biblical narrative, whether God is good, and all of the other questions you would expect. This is part of the problem; these hoary old questions have been rehashed so much that they barely provide anything new on either side. Like two grandmasters playing chess, both sides know the best moves to make and the opening gambits are simply about manouvering. It's only by going deeper that anything actually interesting or challenging can be reached.

This, however, is very much a surface level introduction, and if you're keen to just read one book and be convinced, you probably will be. It's well argued, impeccably sourced and clearly articulated, but it really is only skimming the surface. The chapter on science is no comprehensive rebuttal of The Selfish Gene or God Delusion, the two most prominent critiques of religion from Dawkins, which would be the kind of thing any Christian faced with this question in real life would need to answer.

In fact, much of its muscle comes from a reliance on Biblical exegesis and authority, a difficult position to maintain if the reader doubts the inerrancy of that text. This leaves it in a halfway house of trying to prove the Bible, whilst asserting the relevance of the Bible as the ur-text and proof. Neither legally rigorous or logically consistent, this is best read as an introduction, for a few snappy soundbites and quotes, and then moved on from, swiftly.

Also Try:

Lee Strobel, Case for Christ

Richard Dawkins, God Delusion

Karen Armstrong, The Bible: A Biography

Tom Wright, Creation, Power and Truth

Sunday, October 26, 2014

Down And Out In Paris And London, George Orwell

"This unusual fictional account, in good part autobiographical, narrates without self-pity and often with humor the adventures of a penniless British writer among the down-and-out of two great cities. In the tales of both cities we learn some sobering Orwellian truths about poverty and society."

Britain's most eminent author, or, if you're Will Self, mediocrity, Orwell's fiction often gets most of the praise, but it's his insightful social commentary which is the best place to start anyone interested in him as a writer. Whilst 'Animal Farm' and '1984' are better known and more highly regarded, it's in the books of social commentary and biography that his humanity is based.

Down and Out is the chronicle of Orwell's time destitute in the capitals of France and England, a time spent doing mind-numbing jobs or back breaking labour for very little pay, or living on the streets as a tramp.

Whilst much of it is interesting, especially during his time in Paris working in the kitchens and back rooms of the hotels and restaurants, it's once he gets to London and hits the real bottom of the socio-economic ladder that this becomes more than just a dry recourse of events. His heartfelt telling of the plight of those ignored by scoiety, cheated by the system and left to rely on demeaning charity handouts is as timely now, in an age where the social safety net is fraying and homelessness on the rise, as it was then. His insight, and the humanising of callously overlooked human beings, is a vital part of recognizing that there's an issue. Most tellingly, he debunks many of the myths that still cling to poverty; of abuse of the system, and of personal responsibility for their own misfortune, myths that paint victims as perpetrators and seek to maintain an abusive status quo.

Really good reading.

Also Try:

George Orwell, Homage to Catalonia

George Orwell, Animal Farm

Karl Marx, The Communist Manifesto

Down and Out is the chronicle of Orwell's time destitute in the capitals of France and England, a time spent doing mind-numbing jobs or back breaking labour for very little pay, or living on the streets as a tramp.

Whilst much of it is interesting, especially during his time in Paris working in the kitchens and back rooms of the hotels and restaurants, it's once he gets to London and hits the real bottom of the socio-economic ladder that this becomes more than just a dry recourse of events. His heartfelt telling of the plight of those ignored by scoiety, cheated by the system and left to rely on demeaning charity handouts is as timely now, in an age where the social safety net is fraying and homelessness on the rise, as it was then. His insight, and the humanising of callously overlooked human beings, is a vital part of recognizing that there's an issue. Most tellingly, he debunks many of the myths that still cling to poverty; of abuse of the system, and of personal responsibility for their own misfortune, myths that paint victims as perpetrators and seek to maintain an abusive status quo.

Really good reading.

Also Try:

George Orwell, Homage to Catalonia

George Orwell, Animal Farm

Karl Marx, The Communist Manifesto

On Basilisk Station, David Weber

"HONOR HARRINGTON

I've long wanted to read David Weber's 'Honor Series'; it's ubiquity in some form or another in charity shops points to a wide fanbase, but until recently I never found a copy of the first in the series, 'On Basilik Station'. It was well worth the wait, and I'm very keen to read the next book.

The Baen business model is fascinating, and their commitment to freeshare books is one that's exceptional in its fairness and earned scruples. The first half dozen books in the series are currently available online to read for free, or to download to Kindle for a pittance. It allows new readers to get into the series easily, and the accessibility encourages hooked readers to continue reading by picking up a full price book.

This is an excellent idea, and for a series that is currently pushing 15 books, an easy way to entice readers into commiting to a series without breaking their bank account. It also allows for Bain to see the interest levels in their stories.

It helps that the books are fantastic, a roaring alternative to Sharpe or Hornblower set in the far future, but with a tactical and military side that does a far better job of recognizing the range and scale of space conflict than almost any other book I've read, aside from maybe Iain M Banks' Culture novels.

Honor herself is a wonderful character, a strong female protagonist with a novel back story and charisma, charm and chutzpah in spades. The villains are unsubtley written, as is the case for almost all books of this style, but that's part of the fun - and fun it is, to an almost ridiculous degree.

Also Try:

David Weber, On Basilisk Station - http://www.baenebooks.com/p-304-on-basilisk-station.aspx

Iain M. Banks, Player of Games

Orson Scott Card, Ender's Game

Having made him look a fool, she's been exiled to Basilisk Station in disgrace and set up for ruin by a superior who hates her.

Her demoralized crew blames her for their ship's humiliating posting to an out-of-the-way picket station.

The aborigines of the system's only habitable planet are smoking homicide-inducing hallucinogens.

Parliament isn't sure it wants to keep the place; the major local industry is smuggling; the merchant cartels want her head; the star-conquering, so-called "Republic" of Haven is Up To Something; and Honor Harrington has a single, over-age light cruiser with an armament that doesn't work to police the entire star system.

But the people out to get her have made one mistake. They've made her mad."

I've long wanted to read David Weber's 'Honor Series'; it's ubiquity in some form or another in charity shops points to a wide fanbase, but until recently I never found a copy of the first in the series, 'On Basilik Station'. It was well worth the wait, and I'm very keen to read the next book.

The Baen business model is fascinating, and their commitment to freeshare books is one that's exceptional in its fairness and earned scruples. The first half dozen books in the series are currently available online to read for free, or to download to Kindle for a pittance. It allows new readers to get into the series easily, and the accessibility encourages hooked readers to continue reading by picking up a full price book.

This is an excellent idea, and for a series that is currently pushing 15 books, an easy way to entice readers into commiting to a series without breaking their bank account. It also allows for Bain to see the interest levels in their stories.

It helps that the books are fantastic, a roaring alternative to Sharpe or Hornblower set in the far future, but with a tactical and military side that does a far better job of recognizing the range and scale of space conflict than almost any other book I've read, aside from maybe Iain M Banks' Culture novels.

Honor herself is a wonderful character, a strong female protagonist with a novel back story and charisma, charm and chutzpah in spades. The villains are unsubtley written, as is the case for almost all books of this style, but that's part of the fun - and fun it is, to an almost ridiculous degree.

Also Try:

David Weber, On Basilisk Station - http://www.baenebooks.com/p-304-on-basilisk-station.aspx

Iain M. Banks, Player of Games

Orson Scott Card, Ender's Game

Monday, October 13, 2014

America Alone; The End Of The World As We Know It, Mark Steyn

"It's the end of the world as we know it...Someday soon, you might wake up to the call to prayer from a muezzin. Europeans already are. And liberals will still tell you that "diversity is our strength"--while Talibanic enforcers cruise Greenwich Village burning books and barber shops, the Supreme Court decides sharia law doesn't violate the "separation of church and state," and the Hollywood Left decides to give up on gay rights in favor of the much safer charms of polygamy. If you think this can't happen, you haven't been paying attention, as the hilarious, provocative, and brilliant Mark Steyn shows to devastating effect. The future, as Steyn shows, belongs to the fecund and the confident. And the Islamists are both, while the West is looking ever more like the ruins of a civilization. But America can survive, prosper, and defend its freedom only if it continues to believe in itself, in the sturdier virtues of self-reliance (not government), in the centrality of family, and in the conviction that our country really is the world's last best hope."

Mark Steyn's America Alone is the kind of book that I pick up every now and then and read in the same way Southern schools approach creationism and evolution; it's reading the controversy, Frankly, if the above quote doesn't represent it enough, American Alone is a brilliantly though out, well argued and utterly incorrect assertion that Islam is on an unstoppable path to taking over Europe and the world.

There's so much wrong about this that even the stuff that's genuinely interesting and important can be ignored; the work on demographics, and attempt to get beyond the stale arguments between conservative and liberals about Islam to talk about what Islam itself believes is good, but too often if becomes bogged down in reactionary dogma and xenophobic spite.

If you've seen Affleck vs Maher recently, you'll know the thrust of the argument; Islam is a threat not just to conervative ideology but liberal too, there's more of them every year and less of us, and sooner of later their ideas win democratically because they can muster the only voices. It all relies on an us-them attitude, and ignores pretty much anything on progressive or liberal voices within Islam, but it's an argument that seems to be growing in popularity and prominence.

It's worth reading then, if only to be able to refute it, and to quote it in disbelief to incredulous friends.

Also Try:

This American Life: A Not So Simple Majority; http://www.thisamericanlife.org/radio-archives/episode/534/a-not-so-simple-majority

Mark Steyn's America Alone is the kind of book that I pick up every now and then and read in the same way Southern schools approach creationism and evolution; it's reading the controversy, Frankly, if the above quote doesn't represent it enough, American Alone is a brilliantly though out, well argued and utterly incorrect assertion that Islam is on an unstoppable path to taking over Europe and the world.

There's so much wrong about this that even the stuff that's genuinely interesting and important can be ignored; the work on demographics, and attempt to get beyond the stale arguments between conservative and liberals about Islam to talk about what Islam itself believes is good, but too often if becomes bogged down in reactionary dogma and xenophobic spite.

If you've seen Affleck vs Maher recently, you'll know the thrust of the argument; Islam is a threat not just to conervative ideology but liberal too, there's more of them every year and less of us, and sooner of later their ideas win democratically because they can muster the only voices. It all relies on an us-them attitude, and ignores pretty much anything on progressive or liberal voices within Islam, but it's an argument that seems to be growing in popularity and prominence.

It's worth reading then, if only to be able to refute it, and to quote it in disbelief to incredulous friends.

Also Try:

This American Life: A Not So Simple Majority; http://www.thisamericanlife.org/radio-archives/episode/534/a-not-so-simple-majority

Blankets, Craig Thompson

"At 592 pages, Blankets may well be the single largest graphic novel ever published without being serialized first. Wrapped in the landscape of a blustery Wisconsin winter, Blankets explores the sibling rivalry of two brothers growing up in the isolated country, and the budding romance of two coming-of-age lovers. A tale of security and discovery, of playfulness and tragedy, of a fall from grace and the origins of faith. A profound and utterly beautiful work from Craig Thompson."

Blankets is the exact kind of book that libraries were made for; a sweepingly original, beautiful and heartfelt novel of teenage love, loss and identity that I would never ever pick up but which is utterly wonderful.

Blankets is tonally atypical of almost anything else out there, working as much as a late teen reimagining of Calvin and Hobbes or a less magical-realism Scott Pilgrim. Both of these featured protagonists stuck in their own heads, and Thompson's autobiographical tale is sweetly familiar for this. The constantly present snow covers up as much as he reveals with Blankets, but it's not just art school drawing and introspection, as there's a throughline of humour that he mines to great effect, with one passage in particular, of Thompson and his brother pretending to pee on one another leaving me in stitches.

It's maybe more funny in context.

This is a medium-pushing work, a book with heft and weight beyond just its size. This is a far more important, refreshing and thoughtful work about being a teenager than Catcher in the Rye could ever hope to be,

Also Try;

Daniel Clowes, Ghostworld

Bill Watterson, Calvin and Hobbes

Bryan Lee O'Malley, Scott Pilgrim

Blankets is the exact kind of book that libraries were made for; a sweepingly original, beautiful and heartfelt novel of teenage love, loss and identity that I would never ever pick up but which is utterly wonderful.

Blankets is tonally atypical of almost anything else out there, working as much as a late teen reimagining of Calvin and Hobbes or a less magical-realism Scott Pilgrim. Both of these featured protagonists stuck in their own heads, and Thompson's autobiographical tale is sweetly familiar for this. The constantly present snow covers up as much as he reveals with Blankets, but it's not just art school drawing and introspection, as there's a throughline of humour that he mines to great effect, with one passage in particular, of Thompson and his brother pretending to pee on one another leaving me in stitches.

It's maybe more funny in context.

This is a medium-pushing work, a book with heft and weight beyond just its size. This is a far more important, refreshing and thoughtful work about being a teenager than Catcher in the Rye could ever hope to be,

Also Try;

Daniel Clowes, Ghostworld

Bill Watterson, Calvin and Hobbes

Bryan Lee O'Malley, Scott Pilgrim

How Not To Be American: Misadventures in the Land of the Free, Tood McEwen

"'This new American uniform - the baseball cap, t-shirt, shorts and trainers (why not a scooter?) is not about looking good. It's about disappearing into a new, unofficial, global army of cultural babies. It says: I eat hamburgers and watch TV and chew gum all day, I want everyone to play my game, You have to be nice to me and if you're not I'm gonna shoot you, I can't understand a word you say… and what is that but American foreign policy?' Todd McEwen left the United States in 1980, but it's still driving him crazy. He worries about cheeseburgers, Cary Grant, Henry David Thoreau, democracy, the Elks Club and Daffy Duck. Join him on his acid-reflux examination of what America has come to be."

I approached this anticipating an American version of the anthropology, or at least quasi-anthropology, of something like Kate Fox or Bill Bryson. It's really, really not, Instead, it's McEwen's own take on an autobiography, closer to a series of essays and thoughts on subjects from Cary Grant's suit to california politics.

At one point there's a surrealist dream sequence piece.

It's hella weird, and the schtick gets old well before it ends, with the roughly 60% that's really good being heavily outweighed by the stuff that really isn't.

And it definitively doesn't explain how not be American.

Also Try:

Bill Bryson, A Walk in the Woods

Kate Fox, Watching the English

Barack Obama, Audacity of Hope

I approached this anticipating an American version of the anthropology, or at least quasi-anthropology, of something like Kate Fox or Bill Bryson. It's really, really not, Instead, it's McEwen's own take on an autobiography, closer to a series of essays and thoughts on subjects from Cary Grant's suit to california politics.

At one point there's a surrealist dream sequence piece.

It's hella weird, and the schtick gets old well before it ends, with the roughly 60% that's really good being heavily outweighed by the stuff that really isn't.

And it definitively doesn't explain how not be American.

Also Try:

Bill Bryson, A Walk in the Woods

Kate Fox, Watching the English

Barack Obama, Audacity of Hope

The Catcher in the Rye, J. D. Salinger

"Anyone who has read J. D. Salinger's New Yorker stories - particularly A Perfect Day for Bananafish, Uncle Wiggily in Connecticut, The Laughing Man, and For Esme - With Love and Squalor, will not be surprised by the fact that his first novel is full of children. The hero-narrator of The Catcher in the Rye is an ancient child of sixteen, a native New Yorker named Holden Caulfield. Through circumstances that tend to preclude adult, secondhand description, he leaves his prep school in Pennsylvania and goes underground in New York City for three days. The boy himself is at once too simple and too complex for us to make any final comment about him or his story. Perhaps the safest thing we can say about Holden is that he was born in the world not just strongly attracted to beauty but, almost, hopelessly impaled on it. There are many voices in this novel: children's voices, adult voices, underground voices-but Holden's voice is the most eloquent of all. Transcending his own vernacular, yet remaining marvelously faithful to it, he issues a perfectly articulated cry of mixed pain and pleasure. However, like most lovers and clowns and poets of the higher orders, he keeps most of the pain to, and for, himself. The pleasure he gives away, or sets aside, with all his heart. It is there for the reader who can handle it to keep."

The so called 'teen bible', Catcher in the Rye is often branded as the most important and true-to-youth book ever written, which makes coming to it as an adult potentially the wrong way to do it. It's easy to see why teens love it, it is utterly a teen novel, in the sense that it's meandering, boring and more impressed with itself than it should be.

It is a relentlessly teen read; a book that so thoroughly nails the self-important conceit of being young and certain that you're better than everyone else. Everything from his distaste of the phony's that surround him, to the disinterest in his education and future make Holden's voice uniquely and authentically spot-on.

Unfortunately, you would be better off skipping it, as that same authenticity makes it virtually impossible to like him. He's an unrepentent little dick; the kind of kid whose self-satisfied selfishness is the attitude you hope people will leave behind when they become adults but which, judging by his popularity with killers, some people sadly don't. Like The Great Gatsby, it's a wonderfully constructed portrait of someone you probably want to spend as little time as possible actually in the company of.

To put it into contest; Lord of the Flies is a great book, but would you want to hang out with or emulate the kids from that?

Also Try:

Suzanne Collins, The Hunger Games

Charlie Higson, The Enemy

William Golding, Lord of the Flies

The so called 'teen bible', Catcher in the Rye is often branded as the most important and true-to-youth book ever written, which makes coming to it as an adult potentially the wrong way to do it. It's easy to see why teens love it, it is utterly a teen novel, in the sense that it's meandering, boring and more impressed with itself than it should be.

It is a relentlessly teen read; a book that so thoroughly nails the self-important conceit of being young and certain that you're better than everyone else. Everything from his distaste of the phony's that surround him, to the disinterest in his education and future make Holden's voice uniquely and authentically spot-on.

Unfortunately, you would be better off skipping it, as that same authenticity makes it virtually impossible to like him. He's an unrepentent little dick; the kind of kid whose self-satisfied selfishness is the attitude you hope people will leave behind when they become adults but which, judging by his popularity with killers, some people sadly don't. Like The Great Gatsby, it's a wonderfully constructed portrait of someone you probably want to spend as little time as possible actually in the company of.

To put it into contest; Lord of the Flies is a great book, but would you want to hang out with or emulate the kids from that?

Also Try:

Suzanne Collins, The Hunger Games

Charlie Higson, The Enemy

William Golding, Lord of the Flies

Prime Minister Portillo and other things that never happened, various

"What if Lenin's train had crashed on the way to the Finland Station? Lee Harvey Oswald had missed? Lord Halifax had become Prime Minister in 1940 instead of Churchill? In this diverting and thought-provoking book of counter-factuals a collection of distinguished commentators consider how things might have been."

I find these non-fiction 'What if?' books slightly sad, as they work as neither a truly good history book, or as a work of historical fiction. This is compounded by a mixed bag of authors, who range from those catalogueing slight alterations to full blown changes in the timeline, in a variety of styles, with varying degrees of success.

I find these non-fiction 'What if?' books slightly sad, as they work as neither a truly good history book, or as a work of historical fiction. This is compounded by a mixed bag of authors, who range from those catalogueing slight alterations to full blown changes in the timeline, in a variety of styles, with varying degrees of success.

One of the big issues is that very few of these imagine a world changed all that much by the alterations they describe; most are obscure, or at least historically distant, enough that it's hard to see how a revitalised party or individual could have impacted more. Even greater changes, like JFK surviving or Churchill being passed over for Halifax engender only slight fluctuations - legislation passes slower, or the pace of the war moves differently, with the same fixed outcome.

It's a very Fukuyama-esque book, where the outcome we currently have is seemingly all that's possible. Compare and contrast to real works of speculative history, such as Harry Turtledove, and the difference is huge.

Often dry, sometimes interesting, but only fitfully worth dipping into, this is a book more for the writers than the readers, and is best passed over in favour of better offerings.

Also Try;

Robert Harris, Fatherland

Eric Flint; 1631

Harry Turtledove, Guns of the South

Sunday, October 5, 2014

Code Monkey Save World, Greg Pak and Jonathan Coulton

"A put-upon coding monkey teams up with a seething, lovelorn super-villain to fight robots, office worker zombies, and maybe even each other as they struggle to impress the amazing women for whom they fruitlessly long. Based on the songs of internet superstar musician Jonathan Coulton."

I picked this up from Kickstarter on the strength of being a fan of both Jonathan Coulton, on whose songs the book is based, and Greg Pak, the writer of the story. Growing out of a Twitter conversation between the two about how cool it would be to use the former's songs to create a interconnected Universe, the four issue comic series was hugely succesful and includes a number of extra's, including illustrated song lyrics, mini-comics and throwaway joke panels, as well as sample art from Takeshi Miyazawa.

The story is perfunctory, and serves more as a way of introducing the concepts and themes of Coulton's songs. This can take it in some weird directions, but it doesn't have the scope to do anything more than reference and move along, leaving it a little lost when it tries for epic scale (which, considering it features space war, robot invasions, zombie uprisings and multiple supervillains, is a frequent occurrence).

It's not bad, but it isn't the home run I had hoped for. The art though is lovely, and Code Monkey in particular is wonderfully drawn, with Miyazawa pencilling an expressiveness to every character that's a real treat.

Also Try:

Greg Pak, Incredible Hercules

Bryan Lee O'Malley, Scott Pilgrim

Monday, September 15, 2014

Military Blunders, Saul David

"Retelling the most spectacular cock-ups in military history, this graphic account has a great deal to say about the psychology of military incompetence and the reasons even the most well-oiled military machines inflict disaster upon themselves. Beginning in AD9 with the massacre of Varus and his legions in the Black Forest all the way up to present day conflict in Afghanistan, it analyses why things go wrong on the battlefield and who is to blame."

"Retelling the most spectacular cock-ups in military history, this graphic account has a great deal to say about the psychology of military incompetence and the reasons even the most well-oiled military machines inflict disaster upon themselves. Beginning in AD9 with the massacre of Varus and his legions in the Black Forest all the way up to present day conflict in Afghanistan, it analyses why things go wrong on the battlefield and who is to blame."Jalyss got me this book for Christmas and I finally devoured it before the wedding.

It's exactly what it says on the tin; a look at military blunders. Divided into various chapters focussing on different modes of blunder, from incompetent leaders, to poor planning and intelligence to disastrous excecution.

Some of the stories are tragic, most farcically stupid. Incompetence tends to be a key theme. Many of the same people appear again and again. Churchill appears more often than one might expect.

There's a definite bias towards English disasters, with a very obvious historical bias towards the period of 1850 to 1920 (i.e, Victorian and World War One English military disasters) which is a slight let down, as these are fairly similar in scope and mostly rely on the fact that the Imperial generals underestimated anyone who wasn't white or British.

Still, entertaining, and I learnt some interesting stuff in it, especially the chapter on the American civil war.

Also Try:

Amazon has bout 30 books called Military Blunders, try one of those!

Friday, August 8, 2014

Doctor Sleep, Stephen King

"What happened to Danny Torrance, the boy at the heart of The Shining, after his terrible experience in the Overlook Hotel? The instantly riveting Doctor Sleep picks up the story of the now middle-aged Dan, working at a hospice in rural New Hampshire, and the very special twelve-year old girl he must save from a tribe of murderous paranormals.

"What happened to Danny Torrance, the boy at the heart of The Shining, after his terrible experience in the Overlook Hotel? The instantly riveting Doctor Sleep picks up the story of the now middle-aged Dan, working at a hospice in rural New Hampshire, and the very special twelve-year old girl he must save from a tribe of murderous paranormals.On highways across America, a tribe of people called The True Knot travel in search of sustenance. They look harmless - mostly old, lots of polyester, and married to their RVs. But as Dan Torrance knows, and tween Abra Stone learns, The True Knot are quasi-immortal, living off the 'steam' that children with the 'shining' produce when they are slowly tortured to death.

Haunted by the inhabitants of the Overlook Hotel where he spent one horrific childhood year, Dan has been drifting for decades, desperate to shed his father's legacy of despair, alcoholism, and violence. Finally, he settles in a New Hampshire town, an AA community that sustains him and a job at a nursing home where his remnant 'shining' power provides the crucial final comfort to the dying. Aided by a prescient cat, he becomes 'Doctor Sleep.' Then Dan meets the evanescent Abra Stone, and it is her spectacular gift, the brightest shining ever seen, that reignites Dan's own demons and summons him to a battle for Abra's soul and survival ..."

Stephen King was the author I spent my teenage years reading everything I could find of. From the first time I picked up my Dad's old copies of Carrie and Firestarter, to bargain hunting for the back catalogue and obsessively purchasing new releases, I was utterly hooked. I still have all of my copies, and recently started to replace them with hardbacks (a process which moving to America may interrupt somewhat).

King gave me some of my most enduring memories of literature. I won't ever forget the bittersweet hope of the end of The Mist, or the realisation of the inevitability of the fate of those left on The Raft. Before I waited for the "great bearded glacier", George R. R. Martin, to finish writing A Song of Ice and Fire, I was desperate to know what became of The Gunslinger as he followed the man in black through the many worlds along the beam.

And for all that I think his strength is actually his short stories King has given me enough 1000 page burglar-stunners for me to know he can handle the epic.

True, post-accident there was a drop in form, and a propensity for naval gazing and introspection that marred the end of the quest for the Dark Tower and showed itself most clearly in a series of semi autobiographical leads and a merging of King's life and his stories. This slump certainly seems to have been arrested however, and his last few books (Under The Dome especially) have been, if not instant classic, certainly a response to critics who wrote the master off.

If Doctor Sleep features a little too much of the Stephen King staple template (messed up recovering alcoholic, powerful but troubled children, supernatural villains travelling through small town America) it at least reads as more of a greatest hits than an attempt to repeat former greatness.

As a story it's serviceable, but where it shines (pun unintended) is in the relationship between Danny and Abra, a tale of redemption certainly, but also a more tender story of a man who finally finds his place as a mentor and who learns to face more than just literal demons.

Characterisation is one of Kings strongpoints, alongside world building and dialogue and he creates a convincing and consistent cast with their own motivations and expectations without ever coming across as clichéd.

As good as a stand alone book as it is as a sequel to The Shining, a book I didn't feel the need to reread beforehand, this is return to near-vintage King, and therefore well worth reading.

Also Try;

Stephen King, The Dark Tower books

Stephen King, Skeleton Crew

Dean Koontz, From the Corner of His Eye

Wednesday, August 6, 2014

Eon, Greg Bear

"Above our planet hangs a hollow Stone, vast as the imagination of Man. The inner dimensions are at odds with the outer: there are different chambers to be breached, some even containing deserted cities. The furthest chamber contains the greatest mystery ever to confront the Stone's scientists.

But tombstone or milestone, the Stone is not an alien structure: it comes from the future of our humanity. And the war that breaks out on Earth seems to bear witness to the Stone's prowess as oracle . . ."

If Through Darkest America was unsure whether it wanted to be post-apocalyptic, civil-war epic, Western or teen drama, Eon at least has the virtue of not needing to choose what it is by being everything to all things. It's big sci-fi, hard sci-fi, in the classic vein, with a plot that is followable but not necessarily understandable for all the right reasons.

When the cold war is interrupted by the arrival of a massive meteor, orbiting the Earth, science teams are sent to investigate. At which point every expectation about what's coming next breaks down as Bear decides to just skip over the bits you assume will come next, like the initial reaction to the stone's arrival, or the consequences of a world-ending nuclear war.

This is not a story that's afraid to hit its audience over the head thematically, but it's in the actual science that things can go a bit off the deep end. When your main character is an experimental physicist so brilliant a civilisation literally centuries ahead needs her mind to advance their science you know there's not going to be too much slowing down for the kids at the back to keep up. And so it proves, as the book seeks to set up a mathematical concept allowing a TARDIS to hijack a space rock out of its dimension and back through time. And then there's a space war. Everyone in the book is 'brilliant' in their own way, which can be distracting but is probably more fair in the context of a top secret scientific exploration of future-tech and alien activity.

It makes very little sense but is terrific fun, and works as a wonderful example of truly well thought out xenofiction, up there with anything in the Ender's Game books (a series which did very well at imagining lots of very alien species).

It also has a couple of sequels which I won't be hunting out but would certainly read if I came across them.

Also Try;

Greg Bear, Darwin's Radio

Orson Scott Card, Speaker for the Dead

K. A. Applegate, The Ellimist Chronicles

But tombstone or milestone, the Stone is not an alien structure: it comes from the future of our humanity. And the war that breaks out on Earth seems to bear witness to the Stone's prowess as oracle . . ."

If Through Darkest America was unsure whether it wanted to be post-apocalyptic, civil-war epic, Western or teen drama, Eon at least has the virtue of not needing to choose what it is by being everything to all things. It's big sci-fi, hard sci-fi, in the classic vein, with a plot that is followable but not necessarily understandable for all the right reasons.

When the cold war is interrupted by the arrival of a massive meteor, orbiting the Earth, science teams are sent to investigate. At which point every expectation about what's coming next breaks down as Bear decides to just skip over the bits you assume will come next, like the initial reaction to the stone's arrival, or the consequences of a world-ending nuclear war.

This is not a story that's afraid to hit its audience over the head thematically, but it's in the actual science that things can go a bit off the deep end. When your main character is an experimental physicist so brilliant a civilisation literally centuries ahead needs her mind to advance their science you know there's not going to be too much slowing down for the kids at the back to keep up. And so it proves, as the book seeks to set up a mathematical concept allowing a TARDIS to hijack a space rock out of its dimension and back through time. And then there's a space war. Everyone in the book is 'brilliant' in their own way, which can be distracting but is probably more fair in the context of a top secret scientific exploration of future-tech and alien activity.

It makes very little sense but is terrific fun, and works as a wonderful example of truly well thought out xenofiction, up there with anything in the Ender's Game books (a series which did very well at imagining lots of very alien species).

It also has a couple of sequels which I won't be hunting out but would certainly read if I came across them.

Also Try;

Greg Bear, Darwin's Radio

Orson Scott Card, Speaker for the Dead

K. A. Applegate, The Ellimist Chronicles

The English; A Field Guide, Matt Rudd

"A hilarious field guide to the world’s most remarkable and unusual creatures: the English.

Who are the English? What is this puzzling species? Where does it live? What are its habits? What does it eat? Why does it eat that? And why has it developed such unexotic mating rituals?

Join us on a journey deep into the natural habitat of the English, a journey to rival anything David Attenborough did with gorillas, a journey that begins on a sofa (and continues, unflinchingly, into the kitchen, out into the garden, off to work, down to the pub and then on to the beach… and the bedroom).

Matt Rudd’s fearless anthropological approach leaves no cliché unturned in his attempt to portray the real English. Are we really a nation of binge-drinking, horse-meat-eating, grumbling, tailgating slobs or is there something altogether more beautiful to be found lurking behind the cypress leylandii?

This unprecedented adventure will take you to a DFS store, to Blackpool’s third best B&B, to the coffee kiosk on platform one at 5.35 in the morning. You will step into a ready-meal curry factory, a naturist’s back garden and an office of the future where they do somersaults into beanbags. You will endure a night out in Wakefield, a night out in a queue and a night in Thetford Forest trying, unsuccessfully, to prove that dogging is an urban myth. You will watch Reading play football.

And all from the comfort of your own sofa. How English."

Matt Rudd's The English: A Field Guide is that rare thing that is worse than a Jeremy Clarkson recommendation would suggest, a book that is utterly, shockingly, unfailingly without merit. Presumably some very nice trees were harvested so that this self-indulgent paeon to middle England could be printed, which is a shame because that tree probably provided more insight, wit and value than this book. Matt Rudd is seemingly a journalist. Presumably print media's long anticipated death will be suicide. Sinking any lower is impossible.

From front cover to last page, this is a savage indictment of modern England (and this is, of course, written to show nothing other than England, an England unmoored from Wales, Scotland or Ireland, ignorant of any land outside itself and unwilling to drag itself into the 20th Century, let alone the 21st.

To read the back of the book you would think this were the first book to tackle the pop-anthropology of the English mind, but it isn't. This isn't even a Buzzfeed-esque '30 great things about England' experience. It's the utterly depressing middle-aged masturbation fodder of a man who has escaped from The Times style-guide and decided he's witty enough to carry a whole book. He isn't, and he isn't even glib. He's just a dick on a keyboard.

If 'You Are Shit But I like You' was tedious and repetitive it at least found a natural niche in providing information about the unlovely and hideous. This doesn't have even that, instead trying to masquerade its own importence as a sort of jolly 1950s slide-show of travels around England, with 90% less Punch and Judy shows and children throwing up from consuming an ice cream for the first time, and 100% more shit patriotism.

Hilarious like a door and half as readable. Don't read this, just move on.

Also Try:

Kate Fox, Watching The English

Bill Bryson, Notes From A Small Island

Jeremy Paxman, The English

literally anything else ever written

Women and the Kingdom, Faith and Roger Forster

"What does the Bible really say about women?

Should women be allowed to preach or lead in church?

What about what Paul said?

Women and the Kingdom is the long-awaited book by Faith and Roger Forster tackling the role of women within the Kingdom of God. This book takes you on an historical exploration of the roles of women in the Old, New and early church periods before ending up in the present day.

There is thorough, in-depth exegesis of the passages frequently used to argue the case against women in church leadership."

Anything that can really be said here is kind of irrelevant to be honest.

If you're Christian and Feminist (or just one of those), then you should read this. If you want to know what the Bible really teaches about women, then you should read this. If you have just a passing interest in how language shapes institutions, how institutions shape history, and why this is important. Yep, you guessed it, you should read this.

Look, lets face it. Most people have already come to a decision for themselves about the role of women in the church. At one extreme is the idea that women should be neither seen nor heard, that their authority is non-existent and that their principle role is to produce the next generation of male leaders. At the other extreme is ... well, actually, I'm not sure there IS another extreme. There's the centre, where people think that women should probably be able to play a part, say what they think and take a leadership role if they are qualified, but that's hardly an extremist view. That's barely even a view.

Still, because the argument is so skewed that this reasonable position is presented as aggressive Feminist shit-stirring, it's good to have a book that actually does what many men in positions of authority in the church seem to demand; a Biblically founded reason for women to have a role, born out of an exegesis of the text at hand, and an explanation of how the intent has been misrepresented to push women out of church leadership.

Frankly, this should be required reading for anyone before they go talking about what Paul thought about women, what the Bible really says or whether or not God has made women to be subservient to men.

Also Try:

The Bible

Shane Claiborne, The Irresistable Revolution

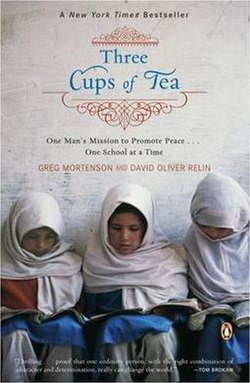

Three Cups of Tea, Greg Mortenson and David Oliver Relin

"'Here we drink three cups of tea to do business; the first you are a stranger, the second you become a friend, and the third, you join our family, and for our family we are prepared to do anything - even die' - Haji Ali, Korphe Village Chief, Karakoram mountains, Pakistan.

In 1993, after a terrifying and disastrous attempt to climb K2, a mountaineer called Greg Mortenson drifted, cold and dehydrated, into an impoverished Pakistan village in the Karakoram Mountains. Moved by the inhabitants' kindness, he promised to return and build a school. "Three Cups of Tea" is the story of that promise and its extraordinary outcome. Over the next decade Mortenson built not just one but fifty-five schools - especially for girls - in remote villages across the forbidding and breathtaking landscape of Pakistan and Afghanistan, just as the Taliban rose to power. His story is at once a riveting adventure and a testament to the power of the humanitarian spirit."

The weirdest thing about Three Cups of Tea is that it's a hugely enjoyable book until you actually go and read further, because it turns out that everything you've read in this, nominally, non-fiction book is ... Broadly untrue? Vaguely inaccurate? A pack of total lies? Whichever version you go for, it kind of undermines the rest of the narrative. That's a shame, because without the critique Mortenson's story is wonderfully inspiring and compelling.

In 1993, after a terrifying and disastrous attempt to climb K2, a mountaineer called Greg Mortenson drifted, cold and dehydrated, into an impoverished Pakistan village in the Karakoram Mountains. Moved by the inhabitants' kindness, he promised to return and build a school. "Three Cups of Tea" is the story of that promise and its extraordinary outcome. Over the next decade Mortenson built not just one but fifty-five schools - especially for girls - in remote villages across the forbidding and breathtaking landscape of Pakistan and Afghanistan, just as the Taliban rose to power. His story is at once a riveting adventure and a testament to the power of the humanitarian spirit."

The weirdest thing about Three Cups of Tea is that it's a hugely enjoyable book until you actually go and read further, because it turns out that everything you've read in this, nominally, non-fiction book is ... Broadly untrue? Vaguely inaccurate? A pack of total lies? Whichever version you go for, it kind of undermines the rest of the narrative. That's a shame, because without the critique Mortenson's story is wonderfully inspiring and compelling.

A mountaineer who stumbled across a Pakistani village whilst descending K2 and was bought back to health by the people there, promising to return and build them a school as thanks, Mortenson is an unfailingly interesting person to read. For the first half of the story I was enraptured by his account, and the breathless narration by journalist and self-professed Mortensom disciple Relin. The story is vividly told, including history, political commentary and context aplenty, alongside an engaging story of triumph against the odds in building the first school despite opposition from corrupt and desperate Pakistani's and indifferent Americans.

Unfortunately, I then went online and read some of the commentary to the book, which sets the benevolent charity Mortenson founded within a wider narrative of financial mismanagement, endemic internal corruption and absolutely no willingness to address these issues. Mortenson's slacker background and inability (and unwillingness) to work with 'the man' suddenly becomes less endearing and more a flashing warning sign that he absolutely should not be in charge of a multi-million dollar organisation. Anyone who is almost uncontactable most of the time, ignores official forms and works from his gut in selecting staff (all traits which are presented as utterly positive and vital to the success of his mission) are obviously going to become liabilities when millions of dollars disappears with no paper trail or inclination to follow up on where it went.

All of which leaves a sour taste in the mouth even before you discover that the two most electrifying moments in the book; Mortenson's near death on K2 (and subsequent arrival in that first impoverished village) and his kidnap and detention by militants in Pakistan's badlands are utterly false and never took place.

From then on the remainder of the book is somewhat less readable as an accurate account of one mans war on poverty and lack of education.

So, worth a read for a look at international development on a budget, but not an organisation to donate to, and certainly not an example to follow.

Also Try:

Jon Krakauer, http://www.thedailybeast.com/articles/2013/04/08/is-it-time-to-forgive-greg-mortenson.html

Jon Krakauer, Three Cups of Deceit

Joel Connely, http://www.seattlepi.com/default/article/Greg-Mortenson-Three-Cups-of-Me-1356850.php

Also Try:

Jon Krakauer, http://www.thedailybeast.com/articles/2013/04/08/is-it-time-to-forgive-greg-mortenson.html

Jon Krakauer, Three Cups of Deceit

Joel Connely, http://www.seattlepi.com/default/article/Greg-Mortenson-Three-Cups-of-Me-1356850.php

Through Darkest America, Neal Barrett Jr.

"Part of the Isaac Asimov Presents series, this provocative novel is set in a world that nuclear war has almost decimated of cities, technology and large animals. To replace farm livestock, the country's sole source of meat is genetically altered humans, without intelligence or speech. A distant civil war out west, its harsh taxes and harsher collectors, force Howie Ryder to flee his family's Tennessee farm. He falls in with outlaw Pardo, who signs on with a big meat drive only to rustle it and playsand preys onboth sides in running guns. Barrett's SF rendering of this latter-day civil war comes complete with a version of slavery, cavalry charges and a young boy representing the country's coming of age. The romantic narrative skillfully moves from a well-told if familiar story of war and the western frontier to areas of ambiguity and uncertainty that readers are left to answer for themselves."

"Part of the Isaac Asimov Presents series, this provocative novel is set in a world that nuclear war has almost decimated of cities, technology and large animals. To replace farm livestock, the country's sole source of meat is genetically altered humans, without intelligence or speech. A distant civil war out west, its harsh taxes and harsher collectors, force Howie Ryder to flee his family's Tennessee farm. He falls in with outlaw Pardo, who signs on with a big meat drive only to rustle it and playsand preys onboth sides in running guns. Barrett's SF rendering of this latter-day civil war comes complete with a version of slavery, cavalry charges and a young boy representing the country's coming of age. The romantic narrative skillfully moves from a well-told if familiar story of war and the western frontier to areas of ambiguity and uncertainty that readers are left to answer for themselves."This is, it has to be said, one of the weirdest books I've ever read. Not so much for the contents (which are pedestrian) or the style (which is standard) but for the concept behind creating a post-Apocalyptic America which is near indistinguishable from Civil War era America (right down to an actual civil war) and has very little in the way of actual post-Apocalyptic America.