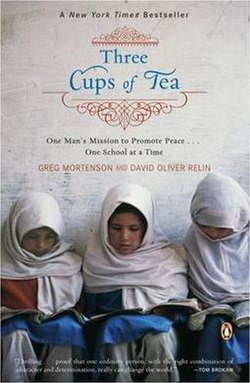

In 1993, after a terrifying and disastrous attempt to climb K2, a mountaineer called Greg Mortenson drifted, cold and dehydrated, into an impoverished Pakistan village in the Karakoram Mountains. Moved by the inhabitants' kindness, he promised to return and build a school. "Three Cups of Tea" is the story of that promise and its extraordinary outcome. Over the next decade Mortenson built not just one but fifty-five schools - especially for girls - in remote villages across the forbidding and breathtaking landscape of Pakistan and Afghanistan, just as the Taliban rose to power. His story is at once a riveting adventure and a testament to the power of the humanitarian spirit."

The weirdest thing about Three Cups of Tea is that it's a hugely enjoyable book until you actually go and read further, because it turns out that everything you've read in this, nominally, non-fiction book is ... Broadly untrue? Vaguely inaccurate? A pack of total lies? Whichever version you go for, it kind of undermines the rest of the narrative. That's a shame, because without the critique Mortenson's story is wonderfully inspiring and compelling.

A mountaineer who stumbled across a Pakistani village whilst descending K2 and was bought back to health by the people there, promising to return and build them a school as thanks, Mortenson is an unfailingly interesting person to read. For the first half of the story I was enraptured by his account, and the breathless narration by journalist and self-professed Mortensom disciple Relin. The story is vividly told, including history, political commentary and context aplenty, alongside an engaging story of triumph against the odds in building the first school despite opposition from corrupt and desperate Pakistani's and indifferent Americans.

Unfortunately, I then went online and read some of the commentary to the book, which sets the benevolent charity Mortenson founded within a wider narrative of financial mismanagement, endemic internal corruption and absolutely no willingness to address these issues. Mortenson's slacker background and inability (and unwillingness) to work with 'the man' suddenly becomes less endearing and more a flashing warning sign that he absolutely should not be in charge of a multi-million dollar organisation. Anyone who is almost uncontactable most of the time, ignores official forms and works from his gut in selecting staff (all traits which are presented as utterly positive and vital to the success of his mission) are obviously going to become liabilities when millions of dollars disappears with no paper trail or inclination to follow up on where it went.

All of which leaves a sour taste in the mouth even before you discover that the two most electrifying moments in the book; Mortenson's near death on K2 (and subsequent arrival in that first impoverished village) and his kidnap and detention by militants in Pakistan's badlands are utterly false and never took place.

From then on the remainder of the book is somewhat less readable as an accurate account of one mans war on poverty and lack of education.

So, worth a read for a look at international development on a budget, but not an organisation to donate to, and certainly not an example to follow.

Also Try:

Jon Krakauer, http://www.thedailybeast.com/articles/2013/04/08/is-it-time-to-forgive-greg-mortenson.html

Jon Krakauer, Three Cups of Deceit

Joel Connely, http://www.seattlepi.com/default/article/Greg-Mortenson-Three-Cups-of-Me-1356850.php

Also Try:

Jon Krakauer, http://www.thedailybeast.com/articles/2013/04/08/is-it-time-to-forgive-greg-mortenson.html

Jon Krakauer, Three Cups of Deceit

Joel Connely, http://www.seattlepi.com/default/article/Greg-Mortenson-Three-Cups-of-Me-1356850.php